The regurgitated mythology surrounding writer and director Nora Ephron would have you believe that she was, if nothing else, a hopeless romantic.

Since her passing in 2012, the much-eulogized, much-imitated, and later, much-skewered Ephron has become a fixture of the public’s cultural imagination, based on a flimsy assumption about her life that is, largely, imagined. Ephron’s most celebrated works, or at least those that induce knee-jerk name recognition, are those which are concerned with romance: When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle, and You’ve Got Mail, the latter which she co-wrote with her sister Delia. Often the heroine in Ephron’s films, Meg Ryan earned herself the mantle of “undisputed queen of rom-coms”—a mantle moviegoers steadily applied to Ephron (and Nancy Meyers), too. Her association with matters of the heart was implied, if not screeched by some schmuck like Harry running around the streets of New York.

But the subjects of Ephron’s writing ranged from the size of her breasts to a takedown of egg white omelets—consistent among them, a proclivity for unflinching observation. She peered straight down the barrel of her world and made no exceptions in describing things exactly as she saw them: often with a sense of awe or humor, but more often, with bite. And there is perhaps no greater example of the duality of Ephron’s work—its conflicting cynicism and reluctant idealism—than her only novel, Heartburn.

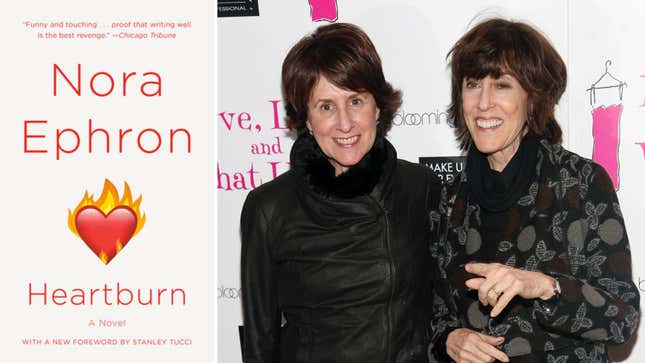

Forty years after its 1983 debut, Heartburn is being re-released by an imprint of Penguin Random House, with an introduction by Stanley Tucci and a new cover (though I imagine Nora might’ve shuttered at the idea of a heart-on-fire emoji as a symbol of her rage). Later adapted into a film starring Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson, the novel was based loosely on Ephron’s marriage to, and ultimate divorce from, journalist Carl Bernstein, who cheated on her while she was pregnant with their second child. When it first published, some critics regarded the work as self-indulgent, the stuff of gossip in which the heroes and villains are sketched in nauseating detail, dirty laundry hung out to dry. What grants Heartburn a seemingly infinite runway into the future, however, is its heartfelt confrontation with relationships: how they buoy us and make us whole, even in the face of their often-inevitable dissolution.

“And soon there’s nothing left of the marriage but the moments of irritation, followed by the apologies, followed by the moments of irritation, followed by the apologies; and all this is interspersed with decisions about which chair goes in the den and whose dinner party are we going to tonight,” Ephron writes.

Barring some too-casual fatphobia and racism, what endears a new generation of readers like me to Ephron’s decades-old revenge novel is its familiarity: the motions of falling in love, the gradual loss of self in partnership, the mundanities of domesticity, and the martyrdom of giving up a body for motherhood. As with Ephron, the novel’s main character Rachel Samstat seems to believe, to her own detriment, that love is worth something—that pursuing it, delusional as it may be, makes sense of our otherwise nonsensical lives.

Despite her tendency towards the acidic, Ephron returned to the romantic over and over again throughout the course of her career, always with a smirk. Her earlier frigid documentation of people and their interactions surely eroded that romanticism over the years. But then there’s moments like this—“I look out the window and I see the lights and the skyline and the people on the street rushing around looking for action, love, and the world’s greatest chocolate chip cookie, and my heart does a little dance”—that remind us Nora Ephron, however begrudgingly, did believe in the life-ruining act of falling in love.

To celebrate 40 years of Heartburn and the life and work of Nora Ephron, Jezebel spoke to the author’s sister and frequent collaborator, Delia Ephron, about love, revenge, and one of Nora’s greatest loves: food.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

You and Nora shared your love of writing, of course. But I’d love to hear a little bit more about the family’s dynamic.

There are four of us sisters, and we’re all published writers. My sister Amy, who’s the youngest, writes period novels, as well as children’s chapter books. And my sister Hallie writes mysteries. And then I write pretty much everything I can think of. And Nora, well, you know all about her. Nora and I were very close when we were young. Nora used to say to everyone that we shared half a brain, but really, the other halves were very different: Nora was a very outgoing, extroverted kind of person and headed for the top from the day she was born. It was like she was shot out of a cannon. Watching her ascent was an amazing thing to experience.

What did Nora mean to you, as a sister?

I think writers are writers first—that’s sort of a calling, and if you are a writer, it’s where you find a kind of peace and happiness and expression. But I’m a sister first, as well. My mother really wasn’t very mothering, so I got an enormous amount of mothering from Nora. She was a person I confided in, she taught me the facts of life, I went to her with my problems my whole life, and she really comforted me. As sisters, I was very dependent on Nora for a kind of mothering that I wasn’t getting in the house.

Your paths meandered—sometimes together, sometimes apart, depending on the year. How did that impact your connection?

We were always connected. We were on the phone once a week. But then also, Nora knew how to do everything, so I had to call her up all the time and say, “Which side of the ham is up?” And she would tell you. Nora just knew everything there was to know. I think that’s one of the things that I love about Heartburn. It’s written by somebody who is so full of stuff to say: about being married, about being cheated on, about being single, about the way people behave. It’s all out there.

In this novel, food serves as a central narrative device, as well as a stand-in for hard-to-swallow emotions. But food seems to pop up in a lot of your work, too, including your book How to Eat Like a Child: And Other Lessons in Not Being a Grown-up. You once said, “I read and I write. Oh, also eating; that’s a very big occupation for me.” Was the act of sitting down to eat an integral part of being an Ephron kid?

We grew up in Beverly Hills, my parents were screenwriters, and they wrote together. My mother was a working woman, something she loved about herself, and all she ever told us was, “You will grow up, and you will have a career. You will have a career. You will have a career!” She never mentioned anything else, pretty much. Even when it came to marriage, she’d tell us, “Elope!” This was the ’50s, so the other mothers did not work, but my mother was just so proud of herself.

Though she didn’t cook much, my mother did make scrambled eggs, and she made them with more butter and slower than anybody in America. She was the sort of person who turned everything she did into this amazing pontification; she’d lecture you about scrambled eggs, you know? [Here Delia imitated her mother’s voice] “When you make scrambled eggs, you must…” So we grew up with a lot of feelings for food before the food revolution took place—something Nora has written about a lot. When everyone really started getting interested in food alongside Craig Claiborne and Julia Child, my mother got very interested in it, too, as did Nora. When you read Heartburn, you can tell that food was much more integral to her life than to any of the rest of the sisters. I mean, we all love food, we all cook, but with Nora, it’s a central thing. And you can see it in the book. Cooking is used not just as an escape, but as punctuation for whatever’s going on: a seduction, a comfort.

Heartburn has been described ad nauseam as a “thinly veiled” story about Nora’s divorce. But as someone who knew Nora better than her readers thought they did, how much of Nora do you see in Rachel Samstat?

Rachel absolutely is Nora. It isn’t all of Nora, but everything Nora thought about at that time of her life is in this book. But that is why it’s so universal: When things are that personal, that’s when they become universal. I have friends who have gone through similar experiences, and that book is a salvation for them, because heartbreak is universal.

One of the things that we were talking about when we did Love, Loss, and What I Wore [the play Delia and Nora wrote together] was that if you ask women about their clothes, they tell you about their life. That became the basis of the play. But the more specific the story, the more it makes other people think about their own lives and what their stories are and what their clothes are. It’s the very specificity of a blue satin dress with the puff sleeves, for example, that makes you think about your prom dress, and then you’re transported to your senior prom, thinking about whatever happened to you. The specificity of Nora’s book will trigger an understanding of your own life.

The genre of romance was an important thread in both your and Nora’s lives, but I’m not sure that rom-coms will ever make their way back to the genre’s golden era, when the Ephron sisters were producing and directing. What do you think is missing from rom-coms today?

What Nora really understood about romantic comedies was that they had to be smart. Their heroines had to be smart. I look back and I think…our movies were smart. I really think that rom-coms should say something about life, and they should say something about men and women and how they get along, like in When Harry Met Sally, which is a masterpiece of Nora’s writing. The most important fact about a romantic comedy is: Why can’t two people be together? That’s the drama you have to solve at the beginning of the romantic comedy. In the case of You’ve Got Mail, it’s for a very smart reason: She owns an independent bookstore, and he’s a big bookstore owner about to put her out of business. Right there, you have what the stakes are, and it puts you in a smart, New York world.

There’s so many romantic comedies where the stakes are too simple, like when two people can’t be together because he’s engaged to someone else. That’s not interesting. But you can see in Heartburn especially just how smart Nora was—how she looked around herself, at what was going on in the world, at everybody’s lives, at everybody’s marriages, and had something to say about it. Nora was a real observer of human life, and of relationships, and that’s why this book has legs; that’s how you can read a book that’s 40 years old and feel like it’s relevant to your life today. Well, except that nobody’s texting in it.

Is there a part of this book that you would like to direct our audiences’ attention to, or perhaps part of it that you feel is vastly underappreciated?

Well, of course, this is Nora’s book. But she’s not here now, and that’s why I’m doing this. Because I love Nora, and I love this book. I just think it’s about being brave and fierce when everything is stacked against you, which is what you’d feel like if you found out your husband was cheating on you. Despite being a demoralizing but common situation, there’s a kind of spirit and bravery to this book that I think is fabulous. And when you read this book, you hook into the fierceness of Nora’s will and wisdom and wit. Plus, this book is really funny. Nora can be funny when no one else can be. She knows how to be funny and make you laugh. I mean, how wonderful is that?