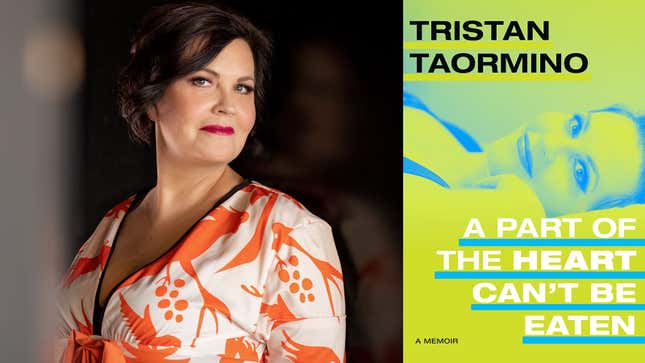

Sex-writer legend Tristan Taormino’s new memoir, A Part of the Heart Can’t Be Eaten, is in part a portrait of the pornographer as a young dyke. It roughly spans her birth in 1971 to 2000, when her career was taking off after she started writing a Village Voice column about her sexual adventures and filmed the award-winning porn movie The Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Women. With candor and clarity, Taormino writes about the journey to becoming a culture-shaping writer and thinker, sparing seemingly few details regarding sexual experiences that defined her, her days at Wesleyan, her femme identity, and her early work. It is often bluntly funny (“Writing and anal sex were my passions”), as well as highly sensitive, particularly in Taormino’s recounting of her experiences with depression, with which she was diagnosed in 1993, and her relationship with her gay father.

Taormino’s remarkable as a second-generation queer person—this is rare, when you consider that many hallmarks of queer culture and the notion of chosen family result from looking outside of one’s biological family. Taormino writes of spending time with her father in Provincetown, absorbing his love of Judy Garland and Barbra Streisand, enduring slights (and in my view, mistreatment) from his partner, and living through his eventual death of AIDS. (Taormino had to sign an agreement never to reach out to her father’s widower in order to inherit some of his property. They haven’t spoken in decades.) In A Part of the Heart Can’t Be Eaten, Taormino prints excerpts from a memoir her father wrote about his upbringing, and there’s a dueting quality to their experiences sitting side by side.

Adding to the queerness of Taormino’s upbringing, she grew up in Sayville, New York, from where the ferries to Fire Island’s gay meccas, the Pines and Cherry Grove, depart. In a way, it seems like she had no shot of becoming anything other than what she did.

In a Zoom interview with Jezebel this week, the “Gen X through and through” Taormino discussed her book, her work, her family (which includes the acclaimed reclusive writer Thomas Pynchon), and her lovers. An edited and condensed transcript of our conversation is below.

JEZEBEL: Did the experience of writing your memoir differ from writing a column about yourself and your sex life?

TRISTAN TAORMINO: I guess on the surface someone could say, “Oh, she’s been writing about herself and about her sexual adventures for decades,” right? It felt very easy and free to share my sexual adventures and some of my personal life in the Village Voice. This book felt totally, totally different. It was pretty terrifying, actually. I went in with the goal of telling the truth, which includes a lot of bad behavior. I mean, I was in my 20s, but, you know. It made me feel really vulnerable in a way that being naked in public does not.

You found your version of nudity.

This is my freaking out about being completely naked in front of everyone.

Now that you’ve written it, what are you most disturbed about people reading?

I’m shameless about sex. But I have a lot of shame about my mental health. A lot. And it’s not something that I’ve written that much about. I wasn’t really out about it probably until my 40s, when I talked sort of freely about it, but again, didn’t write about it. Mental health is still really stigmatized. It’s obviously changed since I was diagnosed with depression in 1993. Like, there’s a vast new world of treatments and support and people reclaiming their mental health issues and being quite open about them, like on social media, for example.

One thing that I found missing from the book was any sense of backlash you may have received from your writing, or from doing porn. Was it missing because literally it’s just been that easy for you, or did you keep it out as expression of your shamelessness and a way of refusing to dwell on the negativity that comes with that work?

The book ends when I’m in my early 30s. I wasn’t well-known enough to have backlash. In the next two decades of my life, my 30s and my 40s, and then my early 50s, oh yeah. There’s been a ton of backlash. I mean, there are universities who’ve uninvited me. I’ve been to conferences where other feminists have called me a trafficker of women. I have been routinely dismissed by the right as a porn star. They think that that’s a derogatory term. They think that’s an insult to me, which it’s actually not. It’s like, that’s just a fact. But then also, I’m not a porn star because that really lessens the role of porn stars. I did a few porn movies and I’m a pornographer.

What was the calculus that went into the very sparing use of the unpublished memoir your father wrote and gave to you?

There was a book that I envisioned like a dual memoir. Part of the issue is that [my father’s] memoir ends in 1973, when I’m 2 years old and he’s about to leave my mother, so there’s two decades of our lives together missing, from his point of view. So first of all, it was kind of a timeline problem. I worked with the most amazing editor at [publisher] Duke, and you get these anonymous reader reports and they give you advice. It began to reshape [the dad memoir] as a part of my history, but not the whole thing. I wanted to draw on these parallels, because when I read about some of the stuff my dad went through, whether it was mental health, his relationship with his parents, infidelity, his sexual desire, there’s so many parallels there. It’s a little bit spooky. So it became more about really using the pieces that connected to my story, but still wanting to honor him and his own story, because it’s two generations of queer people in the same family.

Did you have any communication with ex-lovers? Were people aware that they were going to be portrayed in this book and to what extent they are?

Yes. For all the people that I am in touch with or I could get in touch with, I sent them an email. I sent them the chapter or chapters that they are in. I asked a few questions. One: “Can I use your actual first name? And if not, I’ll change your name.” Two: “Can I use this picture of you and me?” And three: “Do you have any feelings or thoughts that you want to share with me about this chapter or this writing?” Surprisingly, everyone was really great about it on several levels. Most people did not want me to use their real first name. Most people that I had partnered with in the past lead very different lives than I do. They have like, high-power jobs. They have kids and families. Their trajectory didn’t veer towards mine at all. And so, of course, I want to respect people’s privacy. Most people said, “Don’t use my picture,” so I just want to really appreciate the people in my life who were like, “Use my name and use these pictures,” especially my ex-girlfriend, Red, who there are several pictures of and who, in fact, is quite well known in the leather community. There are people I couldn’t track down from high school, and I couldn’t track down Maddy, who was a lover from San Francisco. And of course, I’m not in touch with my father’s widower at all.

Even though that part of the memoir was painful, I thought you were fair to your father’s widower. I thought you were also very fair to Matt, the student teacher in your high school that you had sex with. I think that incident is the closest you come to describing a violation of consent when you’re younger, but it’s not portrayed as this traumatic incident that damaged your life. In fact, you write about the good you were able to glean from this illicit sex, and you move on.

I understand what you’re getting at, because I do believe that that is a chapter people will read and have multiple interpretations. I’m fully prepared for that. I’m fully prepared for people to say, “There was a power dynamic and there was an age difference. There was no possible way you could consent, so it was not consensual.” I’m prepared for people to say, “That’s a sexual assault.” I’m prepared for people to say, “You’re in denial that that was a positive experience for you.”

If you’re not traumatized, you’re not traumatized.

I’m not traumatized. I think that there are also critiques to be made about these relationships wherein power plays such a huge role—there are a lot of really bad situations that people get into with older, powerful figures in their lives when they’re younger, especially women. I just wanted to capture what it was to me and how I feel about it in hindsight, which is an ultimately positive experience. The thing that sucked about that relationship the most was the secrecy.

Similarly audacious is the way that you portray your sexuality as a child, masturbating at age 5, or the sexual contact that you had when you were underage. All of that seems like a potential minefield in 2023.

I don’t have proof of this, but I got a lot of rejections for this book. I began to think, “Is the sex stuff too much?” This is a book about sex, but it’s a book about family and chosen family and queerness and my femme identity and activism and the sex-positive movement. It’s about a lot of things: death, grief. I feel like sometimes people get bogged down when they read the sex thing and immediately kind of shut off. I just wonder if that was a factor in any of the rejections that I got. No one would say that, of course, but I wonder if it’s still too taboo for people. And also, mainstream writing out there about butch/femme dynamics, about kinky dynamics, about queer daddy/girl play—it’s not like I have a lot of models here to go by. It’s not like I can be like, “Oh, that whole scene where I suck her strap-on dick. Yeah, I mean, that’s been in, like, I don’t know, 20 or maybe 40 books.” This will be a little eye-opening for some people, maybe.

I think that something else that might be eye-opening is your adoption of the dyke identity while having sex with men.

I was ambivalent about that at the time period that this book covers. It took me a while to be super out about being a dyke who sleeps with men. I was shamed for that by partners. In some cases I put that piece of myself on a shelf for a really long time in service of another person’s desires in the relationship. Now I feel really strongly that I won’t have anyone in my life, and I certainly won’t partner with anyone, who has any fucking issue with my sexuality. I get tested. I’m transparent. I practice safer sex. If it’s just the very issue that I’m fucking some man, a stranger or a known person? Dealbreaker for me. Also going back and sleeping with cis men now versus back in the day, the sex is so much better, because I know what I want and I think I have a good picker.

Why do you prefer “dyke” over “bisexual?”

For me, “queer” and “dyke” are about history, about the moment in which I came out, which was heavily influenced by queer culture of the ‘90s, by Queer Nation and Act Up, our real politicized identity. That just fit. In fact, recently someone wrote a headline about me where they called me a lesbian and I was a little bit like [cringes]. I just tweaked a little. That doesn’t feel right and doesn’t fit for me because to me, “dyke” captures it all. It captures not only who I love and fuck and partner with, but whom I’m in community with and my politics. I used to say back in the day that I didn’t identify as bisexual because there were more than two genders. Bisexual people refute that entirely, like, “That’s never how we defined it.” I guess I’m willing to own up to some of my own internalized biphobia. I think we all have internalized shit. That’s a piece of everything. But to me, “queer” is just so expansive and encompassing. It just feels more like me.

I love that your uncle Thomas Pynchon makes some cameos in the book, as he has on The Simpsons.

He’s known to elude the media. Like, the photograph they run is his college yearbook photo from Cornell. He is notoriously very, very private, perhaps one of the great reclusive literary minds of our time. This gets back to the issue of one, not capitalizing on that relationship, which would be shitty, and two, not wanting to violate his privacy. And of course, I know things about him. This isn’t in the book, but at some point he lived with my mom and me. He was like, between places or something, and so he lived with us when I was a baby, when I was young. Especially when I was younger, I had a lot of contact with him. The truth is, he did stand out to me in my family as the most similar to me. He was a weirdo and he was eccentric and he was brilliant and he was affectionate in a way that none of the other people on that side of my family were. I felt drawn to him just automatically. That’s why he is identified in my book as Uncle Tom, because to me, he’s Uncle Tom.

Are you still in touch?

Yeah, I sent him the book. I look forward to hearing from him.